A computer-assisted needle misses its target, puncturing the spine. A diabetic patient goes rapidly downhill after a computer recommends an incorrect insulin dosage. An ultrasound fails to diagnose an obvious heart condition that is ultimately fatal.

These are just a few examples of incidents reported to the United States’ Food and Drug Administration involving health technology assisted by artificial intelligence (AI), and Australian researchers say they are an “early warning sign” of what could happen if regulators, hospitals and patients don’t take safety seriously in the rapidly evolving field.

“This is essentially showing us that when we’re putting in AI systems, we just need to be taking the safety of these systems really seriously,” Professor Farah Magrabi said.

Her team at the Australian Institute of Health Innovation at Macquarie University this month published a review of 266 safety events involving AI-assisted technology reported to the US watchdog. The article appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association.

Only 16 per cent actually led to patients being harmed, but two-thirds were found to have the potential to cause harm, and 4 per cent were categorised as “near-miss events” in which users intervened.

Co-author Dr David Lyell said issues arose most commonly when users failed to enter the correct data, leading to an incorrect result, or misunderstood what the AI was actually telling them when it produced a result.

For example, one patient suffering a heart attack delayed medical care because an over-the-counter electrocardiogram device – which is not capable of detecting a heart attack – told them they had “normal sinus rhythm”.

“AI isn’t the answer; it’s part of a system that needs to support the provision of healthcare. And we do need to make sure that we have the systems in place that supports its effective use to promote healthcare for people,” Lyell said.

The researchers chose to analyse cases in the US, where the implementation of AI-enabled health devices is more advanced than in Australia. The US regulator has, to date, approved 521 artificial intelligence and machine learning-enabled medical devices, with 178 of those added in 2022.

In Australia, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) does not collect data about the number of approved devices in Australia that have AI or machine-learning components, but Magrabi said the regulator was taking the issue “very, very seriously”.

“AI isn’t the answer, it’s part of a system that needs to support the provision of health care.”

David Lyell, Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Macquarie University

AI has been used in healthcare devices for decades, but an explosion in data collection, computing power and advanced algorithms has opened up new frontiers, said David Hansen, chief executive of the CSIRO’s Australian E-Health Research Centre.

Sydney-based medical device start-up EMVision is one Australian company taking advantage of these advancements to develop a portable device for diagnosing stroke without the need for an MRI.

In the development stage, the company is using an advanced algorithm and high-powered computers to simulate stroke in numerous places in the brain, building up a database of synthetic images similar to MRIs which are then compared with real-life MRI and CT results from hospital clinical trials at Royal Melbourne, Liverpool and Princess Alexandra hospitals.

“We wouldn’t be able to do what we’re doing today if we didn’t have the [high-powered computer] infrastructure for the simulation,” said head of product development Forough Khandan.

Co-founder Scott Kirkland said the intention was not to completely replace CT and MRI scans, but to diagnose stroke in the first hour when treatment is most effective. The bedside device, set to be launched in 2025, will use a “traffic light” system based on a probability algorithm to help determine what type of stroke might have occurred.

“It’s better for an algorithm to give an ‘I don’t know’ than an incorrect answer, and have the wrong treatment and or triage process followed,” Kirkland said.

Radiology is at the forefront of the rapid adoption of AI in healthcare, especially in breast cancer screening and analysis of chest X-rays.

“A couple of years ago, almost no radiologist would say they use it, now a fair percentage would say that they use it in their daily work,” said clinical radiologist and AI safety researcher Dr Lauren Oakden Rayner.

Rayner, a member of the college, said the technology had many potential benefits, but Australian regulators and clinicians needed to better understand the risks of fully autonomous systems before putting them into hospitals, clinics and homes.

“Humans are legally and morally responsible for decision-making, and it’s taking some of that out of human hands,” she said. “There’s no reason autonomous AI systems can’t exist … but they obviously have to be tested very, very tightly.”

News

This Simple Brain Exercise May Protect Against Dementia for 20 Years

A long-running study following thousands of older adults suggests that a relatively brief period of targeted brain training may have effects that last decades. Starting in the late 1990s, close to 3,000 older adults [...]

Scientists Crack a 50-Year Tissue Mystery With Major Cancer Implications

Researchers have resolved a 50-year-old scientific mystery by identifying the molecular mechanism that allows tissues to regenerate after severe damage. The discovery could help guide future treatments aimed at reducing the risk of cancer [...]

This New Blood Test Can Detect Cancer Before Tumors Appear

A new CRISPR-powered light sensor can detect the faintest whispers of cancer in a single drop of blood. Scientists have created an advanced light-based sensor capable of identifying extremely small amounts of cancer biomarkers [...]

Blindness Breakthrough? This Snail Regrows Eyes in 30 Days

A snail that regrows its eyes may hold the genetic clues to restoring human sight. Human eyes are intricate organs that cannot regrow once damaged. Surprisingly, they share key structural features with the eyes [...]

This Is Why the Same Virus Hits People So Differently

Scientists have mapped how genetics and life experiences leave lasting epigenetic marks on immune cells. The discovery helps explain why people respond so differently to the same infections and could lead to more personalized [...]

Rejuvenating neurons restores learning and memory in mice

EPFL scientists report that briefly switching on three “reprogramming” genes in a small set of memory-trace neurons restored memory in aged mice and in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease to level of healthy young [...]

New book from Nanoappsmedical Inc. – Global Health Care Equivalency

A new book by Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc. Founder. This groundbreaking volume explores the vision of a Global Health Care Equivalency (GHCE) system powered by artificial intelligence and quantum computing technologies, operating on secure [...]

New Molecule Blocks Deadliest Brain Cancer at Its Genetic Root

Researchers have identified a molecule that disrupts a critical gene in glioblastoma. Scientists at the UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center say they have found a small molecule that can shut down a gene tied to glioblastoma, a [...]

Scientists Finally Solve a 30-Year-Old Cancer Mystery Hidden in Rye Pollen

Nearly 30 years after rye pollen molecules were shown to slow tumor growth in animals, scientists have finally determined their exact three-dimensional structures. Nearly 30 years ago, researchers noticed something surprising in rye pollen: [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

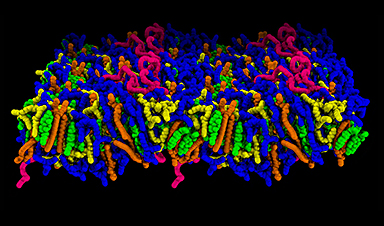

How lipid nanoparticles carrying vaccines release their cargo

A study from FAU has shown that lipid nanoparticles restructure their membrane significantly after being absorbed into a cell and ending up in an acidic environment. Vaccines and other medicines are often packed in [...]

New book from NanoappsMedical Inc – Molecular Manufacturing: The Future of Nanomedicine

This book explores the revolutionary potential of atomically precise manufacturing technologies to transform global healthcare, as well as practically every other sector across society. This forward-thinking volume examines how envisaged Factory@Home systems might enable the cost-effective [...]

A Virus Designed in the Lab Could Help Defeat Antibiotic Resistance

Scientists can now design bacteria-killing viruses from DNA, opening a faster path to fighting superbugs. Bacteriophages have been used as treatments for bacterial infections for more than a century. Interest in these viruses is rising [...]

Sleep Deprivation Triggers a Strange Brain Cleanup

When you don’t sleep enough, your brain may clean itself at the exact moment you need it to think. Most people recognize the sensation. After a night of inadequate sleep, staying focused becomes harder [...]

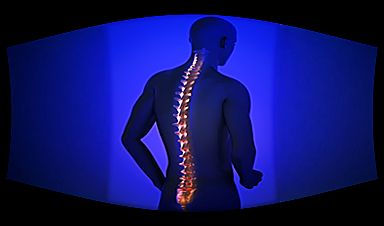

Lab-grown corticospinal neurons offer new models for ALS and spinal injuries

Researchers have developed a way to grow a highly specialized subset of brain nerve cells that are involved in motor neuron disease and damaged in spinal injuries. Their study, published today in eLife as the final [...]

Urgent warning over deadly ‘brain swelling’ virus amid fears it could spread globally

Airports across Asia have been put on high alert after India confirmed two cases of the deadly Nipah virus in the state of West Bengal over the past month. Thailand, Nepal and Vietnam are among the [...]