Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute have identified genetic changes in blood stem cells from frequent blood donors that support the production of new, non-cancerous cells.

Understanding the differences in the mutations that accumulate in our blood stem cells as we age is important to understand how and why blood cancers develop and hopefully how to intervene before the onset of clinical symptoms.

As we age, stem cells in the bone marrow naturally accumulate mutations and with this, we see the emergence of clones, which are groups of blood cells that have a slightly different genetic makeup. Sometimes, specific clones can lead to blood cancers like leukemia.

When people donate blood, stem cells in the bone marrow make new blood cells to replace the lost blood and this stress drives the selection of certain clones.

In research published Blood, the team at the Crick, in collaboration with scientists from the DFKZ in Heidelberg and the German Red Cross Blood Donation Center, analyzed blood samples taken from over 200 frequent donors—people who had donated blood three times a year over 40 years, more than 120 times in total—and sporadic control donors who had donated blood less than five times in total.

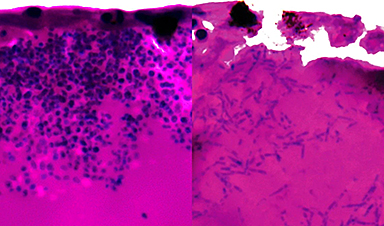

Samples from both groups showed a similar level of clonal diversity, but the makeup of the blood cell populations was different.

For example, both sample groups contained clones with changes to a gene called DNMT3A, which is known to be mutated in people who develop leukemia. Interestingly, the changes to this gene observed in frequent donors were not in the areas known to be preleukemic.

To understand this better, the Crick researchers edited DNMT3A in human stem cells in the lab. They induced the genetic changes associated with leukemia and also the non-preleukemic changes observed in the frequent donor group.

They grew these cells in two environments: one containing erythropoietin (EPO), a hormone that stimulates red blood cell production which is increased after each blood donation, and another containing inflammatory chemicals to replicate an infection.

The cells with the mutations commonly seen in frequent donors responded and grew in the environment containing EPO and failed to grow in the inflammatory environment. The opposite was seen in the cells with mutations known to be preleukemic.

This suggests that the DNMT3A mutations observed in frequent donors are mainly responding to the physiological blood loss associated with blood donation.

Finally, the team transplanted the human stem cells carrying the two types of mutations into mice. Some of these mice had blood removed and then were given EPO injections to mimic the stress associated with blood donation.

The cells with the frequent donor mutations grew normally in control conditions and promoted red blood cell production under stress, without cells becoming cancerous. In sharp contrast, the preleukemic mutations drove a pronounced increase in white blood cells in both control or stress conditions.

The researchers believe that regular blood donation is one type of activity that selects for mutations that allow cells to respond well to blood loss, but does not select the preleukemic mutations associated with blood cancer.

Dominique Bonnet, Group Leader of the Hematopoietic Stem Cell Laboratory at the Crick, and senior author, said, “Our work is a fascinating example of how our genes interact with the environment and as we age. Activities that put low levels of stress on blood cell production allow our blood stem cells to renew and we think this favors mutations that further promote stem cell growth rather than disease.

“Our sample size is quite modest, so we can’t say that blood donation definitely decreases the incidence of pre-leukemic mutations and we will need to look at these results in much larger numbers of people. It might be that people who donate blood are more likely to be healthy if they’re eligible, and this is also reflected in their blood cell clones. But the insight it has given us into different populations of mutations and their effects is fascinating.”

Hector Huerga Encabo, postdoctoral fellow in the Hematopoietic Stem Cell Laboratory at the Crick, and first joint author with Darja Karpova from the DFKZ in Heidelberg, said, “We know more about preleukemic mutations because we can see them when people are diagnosed with blood cancer.

“We had to look at a very specific group of people to spot subtle genetic differences which might actually be beneficial in the long-term. We’re now aiming to work out how these different types of mutations play a role in developing leukemia or not, and whether they can be targeted therapeutically.”

More information: Karpova, D. et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis Landscape in Frequent Blood Donors, Blood (2025). DOI: 10.1182/blood.2024027999

News

The Brain’s Strange Way of Computing Could Explain Consciousness

Consciousness may emerge not from code, but from the way living brains physically compute. Discussions about consciousness often stall between two deeply rooted viewpoints. One is computational functionalism, which holds that cognition can be [...]

First breathing ‘lung-on-chip’ developed using genetically identical cells

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and AlveoliX have developed the first human lung-on-chip model using stem cells taken from only one person. These chips simulate breathing motions and lung disease in an individual, [...]

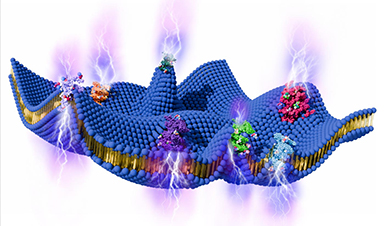

Cell Membranes May Act Like Tiny Power Generators

Living cells may generate electricity through the natural motion of their membranes. These fast electrical signals could play a role in how cells communicate and sense their surroundings. Scientists have proposed a new theoretical [...]

This Viral RNA Structure Could Lead to a Universal Antiviral Drug

Researchers identify a shared RNA-protein interaction that could lead to broad-spectrum antiviral treatments for enteroviruses. A new study from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), published in Nature Communications, explains how enteroviruses begin reproducing [...]

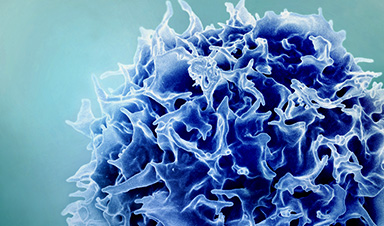

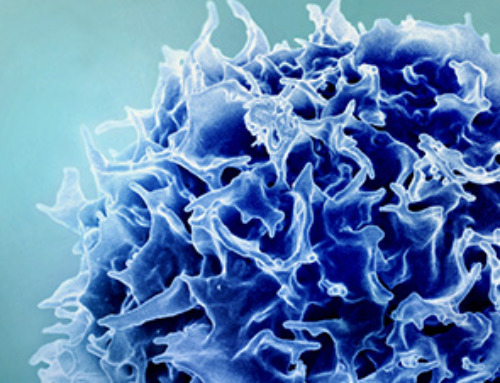

New study suggests a way to rejuvenate the immune system

Stimulating the liver to produce some of the signals of the thymus can reverse age-related declines in T-cell populations and enhance response to vaccination. As people age, their immune system function declines. T cell [...]

Nerve Damage Can Disrupt Immunity Across the Entire Body

A single nerve injury can quietly reshape the immune system across the entire body. Preclinical research from McGill University suggests that nerve injuries may lead to long-lasting changes in the immune system, and these [...]

Fake Science Is Growing Faster Than Legitimate Research, New Study Warns

New research reveals organized networks linking paper mills, intermediaries, and compromised academic journals Organized scientific fraud is becoming increasingly common, ranging from fabricated research to the buying and selling of authorship and citations, according [...]

Scientists Unlock a New Way to Hear the Brain’s Hidden Language

Scientists can finally hear the brain’s quietest messages—unlocking the hidden code behind how neurons think, decide, and remember. Scientists have created a new protein that can capture the incoming chemical signals received by brain [...]

Does being infected or vaccinated first influence COVID-19 immunity?

A new study analyzing the immune response to COVID-19 in a Catalan cohort of health workers sheds light on an important question: does it matter whether a person was first infected or first vaccinated? [...]

We May Never Know if AI Is Conscious, Says Cambridge Philosopher

As claims about conscious AI grow louder, a Cambridge philosopher argues that we lack the evidence to know whether machines can truly be conscious, let alone morally significant. A philosopher at the University of [...]

AI Helped Scientists Stop a Virus With One Tiny Change

Using AI, researchers identified one tiny molecular interaction that viruses need to infect cells. Disrupting it stopped the virus before infection could begin. Washington State University scientists have uncovered a method to interfere with a key [...]

Deadly Hospital Fungus May Finally Have a Weakness

A deadly, drug-resistant hospital fungus may finally have a weakness—and scientists think they’ve found it. Researchers have identified a genetic process that could open the door to new treatments for a dangerous fungal infection [...]

Fever-Proof Bird Flu Variant Could Fuel the Next Pandemic

Bird flu viruses present a significant risk to humans because they can continue replicating at temperatures higher than a typical fever. Fever is one of the body’s main tools for slowing or stopping viral [...]

What could the future of nanoscience look like?

Society has a lot to thank for nanoscience. From improved health monitoring to reducing the size of electronics, scientists’ ability to delve deeper and better understand chemistry at the nanoscale has opened up numerous [...]

Scientists Melt Cancer’s Hidden “Power Hubs” and Stop Tumor Growth

Researchers discovered that in a rare kidney cancer, RNA builds droplet-like hubs that act as growth control centers inside tumor cells. By engineering a molecular switch to dissolve these hubs, they were able to halt cancer [...]

Platelet-inspired nanoparticles could improve treatment of inflammatory diseases

Scientists have developed platelet-inspired nanoparticles that deliver anti-inflammatory drugs directly to brain-computer interface implants, doubling their effectiveness. Scientists have found a way to improve the performance of brain-computer interface (BCI) electrodes by delivering anti-inflammatory drugs directly [...]