A Japanese research team found that the oxidized form of glutathione (GSSG) may protect heart tissue by modifying a key protein, potentially offering a novel therapeutic approach for ischemic heart failure.

A new study by researchers in Japan suggests that the mitochondria, often called the powerhouse of the cell, could be a key target for therapies aimed at mitigating or reversing heart failure.

In experiments using mice and human heart cell lines, the researchers discovered that a molecular marker typically associated with cellular damage may actually have a protective role in the heart, particularly during heart failure. Their findings, published in Nature Communications, identify a specific protein modification that helps safeguard heart tissue in low-oxygen conditions, such as those following a heart attack.

“The primary role of myocardial mitochondria is to sustain high energy production while maintaining intracellular redox balance,” said first author Akiyuki Nishimura, project associate professor in the Division of Cardiocirculatory Signaling at the National Institute for Physiological Sciences (NIPS), one of the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS), in Japan. “Oxidative stress due to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-derived electrophiles is believed to exacerbate the prognosis of ischemic, or low-oxygen, heart diseases.

Mitochondria typically power the cell and help maintain homeostasis by balancing life-sustaining — and potentially ending — oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions. These involve transferring electrons, with the oxidized molecule losing electrons and the reduced one gaining electrons. An imbalance in this exchange can increase oxidative stress, which can lead to cellular damage.

Investigating the Role of GSSG in Heart Protection

“Oxidative stress caused by increased reactive oxygen species production is a key feature of ischemic heart disease and is believed to be involved in the development and progression of heart failure,” Nishimura said. “Therefore, several clinical studies targeting oxidative stress have been performed to improve the outcome of heart failure patients but most of them have failed.”

Rates of oxidative stress are indicated by levels of GSSG, the oxidized form of glutathione (GSH), an antioxidant that helps the body repair damage. In health, there should be much more GSH than GSSG. The lower the ratio between the two molecules, the more GSSG, the more likely there is lasting oxidative damage in the body.

However, Nishimura said, specific studies to investigate if the obvious answer of increasing GSH would improve outcomes have failed.

In this study, the researchers analyzed whether GSSG might be the solution. They found that after heart damage caused by low-oxygen, GSSG modified a sulfur-containing amino acid on a protein called Drp1, protecting mitochondrial function. This protects the heart, the researchers said, because mitochondria can become dysregulated and cause further damage, including heart failure, without enough oxygen.

“These findings prove the breakthrough therapeutic potential of GSSG for ischemic chronic heart failure,” Nishimura said, noting that the team next plans to investigate whether sulfur-based redox reactions have principal roles in disease progression in other organ systems beyond the cardiovascular system.

Reference: “Polysulfur-based bulking of dynamin-related protein 1 prevents ischemic sulfide catabolism and heart failure in mice” by Akiyuki Nishimura, Seiryo Ogata, Xiaokang Tang, Kowit Hengphasatporn, Keitaro Umezawa, Makoto Sanbo, Masumi Hirabayashi, Yuri Kato, Yuko Ibuki, Yoshito Kumagai, Kenta Kobayashi, Yasunari Kanda, Yasuteru Urano, Yasuteru Shigeta, Takaaki Akaike and Motohiro Nishida, 2 January 2025, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-55661-5

Funding: Japan Science and Technology Agency, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, the Joint Research of the Exploratory Research Center on Life and Living Systems, Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, Sumitomo Foundation, Naito Foundation, Smoking Research Foundation

News

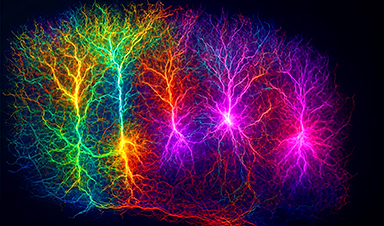

A Grain of Brain, 523 Million Synapses, Most Complicated Neuroscience Experiment Ever Attempted

A team of over 150 scientists has achieved what once seemed impossible: a complete wiring and activity map of a tiny section of a mammalian brain. This feat, part of the MICrONS Project, rivals [...]

The Secret “Radar” Bacteria Use To Outsmart Their Enemies

A chemical radar allows bacteria to sense and eliminate predators. Investigating how microorganisms communicate deepens our understanding of the complex ecological interactions that shape our environment is an area of key focus for the [...]

Psychologists explore ethical issues associated with human-AI relationships

It's becoming increasingly commonplace for people to develop intimate, long-term relationships with artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. At their extreme, people have "married" their AI companions in non-legally binding ceremonies, and at least two people [...]

When You Lose Weight, Where Does It Actually Go?

Most health professionals lack a clear understanding of how body fat is lost, often subscribing to misconceptions like fat converting to energy or muscle. The truth is, fat is actually broken down into carbon [...]

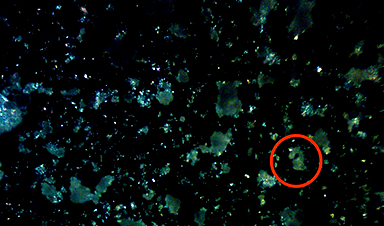

How Everyday Plastics Quietly Turn Into DNA-Damaging Nanoparticles

The same unique structure that makes plastic so versatile also makes it susceptible to breaking down into harmful micro- and nanoscale particles. The world is saturated with trillions of microscopic and nanoscopic plastic particles, some smaller [...]

AI Outperforms Physicians in Real-World Urgent Care Decisions, Study Finds

The study, conducted at the virtual urgent care clinic Cedars-Sinai Connect in LA, compared recommendations given in about 500 visits of adult patients with relatively common symptoms – respiratory, urinary, eye, vaginal and dental. [...]

Challenging the Big Bang: A Multi-Singularity Origin for the Universe

In a study published in the journal Classical and Quantum Gravity, Dr. Richard Lieu, a physics professor at The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH), which is a part of The University of Alabama System, suggests that [...]

New drug restores vision by regenerating retinal nerves

Vision is one of the most crucial human senses, yet over 300 million people worldwide are at risk of vision loss due to various retinal diseases. While recent advancements in retinal disease treatments have [...]

Shingles vaccine cuts dementia risk by 20%, new study shows

A shingles shot may do more than prevent rash — it could help shield the aging brain from dementia, according to a landmark study using real-world data from the UK. A routine vaccine could [...]

AI Predicts Sudden Cardiac Arrest Days Before It Strikes

AI can now predict deadly heart arrhythmias up to two weeks in advance, potentially transforming cardiac care. Artificial intelligence could play a key role in preventing many cases of sudden cardiac death, according to [...]

NanoApps Medical is a Top 20 Feedspot Nanotech Blog

There is an ocean of Nanotechnology news published every day. Feedspot saves us a lot of time and we recommend it. We have been using it since 2018. Feedspot is a freemium online RSS [...]

This Startup Says It Can Clean Your Blood of Microplastics

This is a non-exhaustive list of places microplastics have been found: Mount Everest, the Mariana Trench, Antarctic snow, clouds, plankton, turtles, whales, cattle, birds, tap water, beer, salt, human placentas, semen, breast milk, feces, testicles, [...]

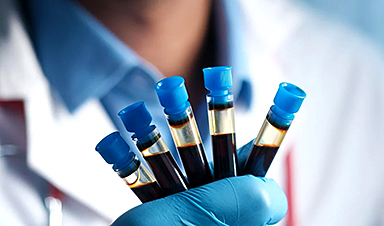

New Blood Test Detects Alzheimer’s and Tracks Its Progression With 92% Accuracy

The new test could help identify which patients are most likely to benefit from new Alzheimer’s drugs. A newly developed blood test for Alzheimer’s disease not only helps confirm the presence of the condition but also [...]

The CDC buried a measles forecast that stressed the need for vaccinations

This story was originally published on ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published. ProPublica — Leaders at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [...]

Light-Driven Plasmonic Microrobots for Nanoparticle Manipulation

A recent study published in Nature Communications presents a new microrobotic platform designed to improve the precision and versatility of nanoparticle manipulation using light. Led by Jin Qin and colleagues, the research addresses limitations in traditional [...]

Cancer’s “Master Switch” Blocked for Good in Landmark Study

Researchers discovered peptides that permanently block a key cancer protein once thought untreatable, using a new screening method to test their effectiveness inside cells. For the first time, scientists have identified promising drug candidates [...]