Antibacterial resistance occurs when antibiotics fail to treat bacterial infections. This incidence is considered one of the top global health threats, stemming from the misuse or overuse of antibiotics in humans and animals.1

The global impact of antibacterial resistance

Bacterial infections are common and can impact various organs and tissues in the human body.² Clinicians typically prescribe antibiotics to treat these infections; however, many bacteria have developed resistance to these treatments, including those considered the “last line of defense,” such as vancomycin and polymyxin. The prevalence of multi-drug-resistant (MDR) bacteria is well-documented.

In 2015, the World Health Organization initiated the Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS) to monitor antimicrobial resistance globally.³ The 2022 GLASS data showed a significant rise in antibiotic resistance, reducing the effectiveness of commonly used antibiotics against widespread bacterial infections.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and third-generation cephalosporin-resistant Escherichia coli (E. coli) have been reported in 76 countries. In 2020, one in five individuals was diagnosed with urinary tract infections caused by E. coli, which showed reduced responsiveness to commonly prescribed antibiotics, including ampicillin, fluoroquinolones, and co-trimoxazole. Additionally, Klebsiella pneumoniae, an intestinal bacterium, exhibited increased antibiotic resistance.³

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) projects a twofold increase in resistance to last-resort antibiotics by 2035. These findings emphasize the urgent need for innovative strategies to combat antibacterial resistance and underscore the importance of expanding global surveillance efforts.

Drug-design strategies to overcome antibacterial resistance

Most currently available antibiotics are derived from discoveries made before 2010. Given the increasing antibacterial resistance to many common antibiotics, there is an urgent need to develop new antibacterial agents that can effectively target a broad range of bacterial strains. Below are some of the key innovative drug-design strategies being explored to address bacterial resistance.

Antimicrobial Peptides (AMPs)

A range of AMPs have been designed to combat bacterial resistance.⁴ For instance, the antibiofilm peptide SAAP-148, derived from the parent peptide LL-37, has shown high efficacy against MDR pathogens.⁵ Proline-rich AMPs (PrAMPs), with multiple intracellular targets and low toxicity, are promising candidates, especially for eliminating Gram-negative pathogens. Commercially available peptide antimicrobials, such as polymyxin and short bacillus peptide, are currently used for therapeutic purposes.

Adjuvants

Efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) and enzymatic inhibitors are commonly used as adjuvants to enhance antibiotic efficacy.⁶ For example, β-lactamase inhibitors are combined with β-lactam antibiotics to prevent the hydrolysis of the antibiotic’s lactam ring, preserving its structural integrity and antibacterial effectiveness.

Efflux pumps contribute significantly to both intrinsic and acquired bacterial resistance.⁷ Current research focuses on identifying and inhibiting EPIs to restore the potency of existing antibiotics. For instance, NorA, a chromosomally encoded multidrug efflux pump in MRSA, can be inhibited with synthetic antigen-binding fragments (Fabs).⁸

Nanomaterials

Metal-based nanomaterials, including zinc, silver, and gold, are utilized for bacterial infection detection and treatment. The antibacterial properties of these nanomaterials depend on their shape, size, and composition. Silver nanoparticles are widely used in biosensing, drug delivery, and antimicrobial wound dressings. Recent research highlights the effectiveness of gold nanoparticles against antibiotic-resistant bacteria.⁹

Cationic polymers, such as chitosan, polyquaternary ammonium salts (PQASs), and polyethyleneimine (PEI), possess intrinsic antibacterial properties.¹⁰ These positively charged materials interact with negatively charged bacterial surfaces, damaging bacterial cell walls or membranes and leading to bacterial cell death.

Phytochemicals

Plants produce secondary metabolites with antibacterial properties, such as phenols, coumarin alkaloids, and organosulfur compounds found in seeds, roots, leaves, stems, flowers, and fruits.¹¹ These compounds are promising candidates for addressing antibacterial resistance.

Plant extracts and essential oils are under study for their potential to modify bacterial antibiotic resistance. Mechanistically, secondary metabolites inhibit efflux pumps, biofilm synthesis, bacterial cell wall synthesis, and bacterial physiology, modulating antibiotic susceptibility. Studies show that alkaloids and phenolic compounds can inhibit the efflux pumps in Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, and MRSA.

RNA silencing

RNA silencing, a natural bacterial gene regulation mechanism, involves complementary cis and trans sequences that interact with regulatory regions on mRNA (antisense sequences). Synthetic antisense sequences can be designed to inhibit the translation of resistance-associated enzymes.¹²

CRISPR-Cas system

The CRISPR-Cas system (clustered regularly interspersed short palindromic repeats-associated protein) is an adaptive immune system in bacteria, protecting against viruses, phages, and foreign genetic material.¹³

As a genetic engineering tool, CRISPR-Cas can selectively target and modify bacterial genomes, potentially reducing or eliminating antibiotic resistance. This strategy shows promise in treating MDR infections.¹⁴

Phage therapy

Although phage therapy has been available for decades, its use declined with the advent of antibiotics. The recent rise in antibiotic resistance has reignited interest in phage therapy. For example, phage therapy successfully treated a cystic fibrosis patient infected with drug-resistant Mycobacteroides abscessus.¹⁵ Bacteriophages have also shown efficacy in treating elderly patients with S. aureus prosthetic joint infections.¹⁶

Drug delivery systems

Drug delivery systems (DDSs) increase antibiotic biodistribution and bioavailability. This strategy can effectively reduce antibiotic resistance and prolong novel antibiotics’ lifespan. Scientists adopted a “Trojan horse” strategy in designing and developing DDSs.

This strategy entails merging antibacterial agents with different carriers, such as exosomes, liposomes, erythrocytes, self-assembled peptides, and polymers. By targeting the unique microenvironment of infected tissue or via external guidance, DDSs enable drug release at the specific site.16

Future research outlook

The availability of various antibiotic types resulted in the development of complex mechanisms of resistance, particularly the emergence of MDR bacteria. To combat the situation, scientists are focused on uncovering the bactericidal mechanism of antibiotics and the mechanism of bacterial resistance.

The advancements in material science, nanotechnology, and gene editing tools have presented multiple opportunities for this strand of research. DDS technology has also exhibited immense potential in helping overcome bacterial resistance in the future.

References

- Mancuso G, et al. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance: The Most Critical Pathogens. Pathogens. 2021;10(10):1310. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10101310.

- Doron S, Gorbach SL. Bacterial Infections: Overview. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. 2008:273–82. doi: 10.1016/B978-012373960-5.00596-7.

- Antimicrobial resistance. World Health Organization; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance. 2023; Assessed on October 5, 2024.

- Xuan J, et al. Antimicrobial peptides for combating drug-resistant bacterial infections. Drug Resistance Updates. 2023; 68, 100954. doi.org/10.1016/j.drup.2023.100954

- Shi J. et al. The antimicrobial peptide LI14 combats multidrug-resistant bacterial infections. Commun Biol. 2022;5, 926. doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03899-4

- El-Khoury C, et al. The role of adjuvants in overcoming antibacterial resistance due to enzymatic drug modification. RSC Med Chem. 2022;13(11):1276-1299. doi: 10.1039/d2md00263a.

- Gaurav A, et al. Role of bacterial efflux pumps in antibiotic resistance, virulence, and strategies to discover novel efflux pump inhibitors. Microbiology (Reading). 2023;169(5):001333. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.001333.

- Brawley DN, et al. Structural basis for inhibition of the drug efflux pump NorA from Staphylococcus aureus. Nat Chem Biol. 2022;18(7):706-712. doi: 10.1038/s41589-022-00994-9.

- Rizvi SMD, et al. Antibiotic-Loaded Gold Nanoparticles: A Nano-Arsenal against ESBL Producer-Resistant Pathogens. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(2):430. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15020430.

- Carmona-Ribeiro AM, de Melo Carrasco LD. Cationic antimicrobial polymers and their assemblies. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(5):9906-46. doi: 10.3390/ijms14059906.

- Ashraf MV, et al. Phytochemicals as Antimicrobials: Prospecting Himalayan Medicinal Plants as Source of Alternate Medicine to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance. Pharmaceuticals. 2023; 16(6):881. doi.org/10.3390/ph16060881

- Jani S, et al. Silencing Antibiotic Resistance with Antisense Oligonucleotides. Biomedicines. 2021;9(4):416. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines9040416.

- Xu Y, Li Z. CRISPR-Cas systems: Overview, innovations and applications in human disease research and gene therapy. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:2401-2415. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.08.031.

- Tao S, et al. The Application of the CRISPR-Cas System in Antibiotic Resistance. Infect Drug Resist. 2022;15:4155-4168. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S370869.

- Recchia D, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus Infections in Cystic Fibrosis Individuals: A Review on Therapeutic Options. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):4635. doi: 10.3390/ijms24054635.

- Yao J, et al. Recent Advances in Strategies to Combat Bacterial Drug Resistance: Antimicrobial Materials and Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(4):1188. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15041188.

News

Differentiating cancerous and healthy cells through motion analysis

Researchers from Tokyo Metropolitan University have found that the motion of unlabeled cells can be used to tell whether they are cancerous or healthy. They observed malignant fibrosarcoma cells and [...]

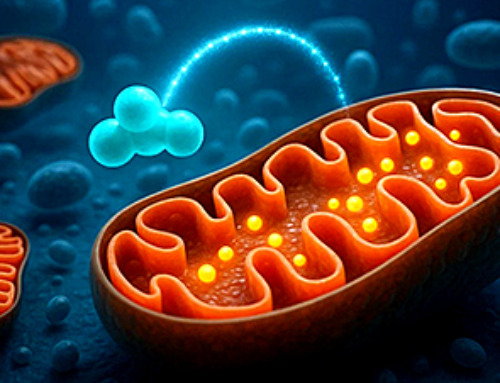

This Tiny Cellular Gate Could Be the Key to Curing Cancer – And Regrowing Hair

After more than five decades of mystery, scientists have finally unveiled the detailed structure and function of a long-theorized molecular machine in our mitochondria — the mitochondrial pyruvate carrier. This microscopic gatekeeper controls how [...]

Unlocking Vision’s Secrets: Researchers Reveal 3D Structure of Key Eye Protein

Researchers have uncovered the 3D structure of RBP3, a key protein in vision, revealing how it transports retinoids and fatty acids and how its dysfunction may lead to retinal diseases. Proteins play a critical [...]

5 Key Facts About Nanoplastics and How They Affect the Human Body

Nanoplastics are typically defined as plastic particles smaller than 1000 nanometers. These particles are increasingly being detected in human tissues: they can bypass biological barriers, accumulate in organs, and may influence health in ways [...]

Measles Is Back: Doctors Warn of Dangerous Surge Across the U.S.

Parents are encouraged to contact their pediatrician if their child has been exposed to measles or is showing symptoms. Pediatric infectious disease experts are emphasizing the critical importance of measles vaccination, as the highly [...]

AI at the Speed of Light: How Silicon Photonics Are Reinventing Hardware

A cutting-edge AI acceleration platform powered by light rather than electricity could revolutionize how AI is trained and deployed. Using photonic integrated circuits made from advanced III-V semiconductors, researchers have developed a system that vastly [...]

A Grain of Brain, 523 Million Synapses, Most Complicated Neuroscience Experiment Ever Attempted

A team of over 150 scientists has achieved what once seemed impossible: a complete wiring and activity map of a tiny section of a mammalian brain. This feat, part of the MICrONS Project, rivals [...]

The Secret “Radar” Bacteria Use To Outsmart Their Enemies

A chemical radar allows bacteria to sense and eliminate predators. Investigating how microorganisms communicate deepens our understanding of the complex ecological interactions that shape our environment is an area of key focus for the [...]

Psychologists explore ethical issues associated with human-AI relationships

It's becoming increasingly commonplace for people to develop intimate, long-term relationships with artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. At their extreme, people have "married" their AI companions in non-legally binding ceremonies, and at least two people [...]

When You Lose Weight, Where Does It Actually Go?

Most health professionals lack a clear understanding of how body fat is lost, often subscribing to misconceptions like fat converting to energy or muscle. The truth is, fat is actually broken down into carbon [...]

How Everyday Plastics Quietly Turn Into DNA-Damaging Nanoparticles

The same unique structure that makes plastic so versatile also makes it susceptible to breaking down into harmful micro- and nanoscale particles. The world is saturated with trillions of microscopic and nanoscopic plastic particles, some smaller [...]

AI Outperforms Physicians in Real-World Urgent Care Decisions, Study Finds

The study, conducted at the virtual urgent care clinic Cedars-Sinai Connect in LA, compared recommendations given in about 500 visits of adult patients with relatively common symptoms – respiratory, urinary, eye, vaginal and dental. [...]

Challenging the Big Bang: A Multi-Singularity Origin for the Universe

In a study published in the journal Classical and Quantum Gravity, Dr. Richard Lieu, a physics professor at The University of Alabama in Huntsville (UAH), which is a part of The University of Alabama System, suggests that [...]

New drug restores vision by regenerating retinal nerves

Vision is one of the most crucial human senses, yet over 300 million people worldwide are at risk of vision loss due to various retinal diseases. While recent advancements in retinal disease treatments have [...]

Shingles vaccine cuts dementia risk by 20%, new study shows

A shingles shot may do more than prevent rash — it could help shield the aging brain from dementia, according to a landmark study using real-world data from the UK. A routine vaccine could [...]

AI Predicts Sudden Cardiac Arrest Days Before It Strikes

AI can now predict deadly heart arrhythmias up to two weeks in advance, potentially transforming cardiac care. Artificial intelligence could play a key role in preventing many cases of sudden cardiac death, according to [...]