Chemical engineers at the University of British Columbia have created a new system that both captures and treats PFAS substances—commonly referred to as "forever chemicals"—in a unified process.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are widely used in manufacturing consumer goods like waterproof clothing due to their resistance to heat, water, and stains. However, they are also pollutants, often ending up in surface and groundwater worldwide, where they have been linked to cancer, liver damage, and other health issues.

"PFAS are notoriously difficult to break down, whether they're in the environment or in the human body," explained lead researcher Dr. Johan Foster, an associate professor of chemical and biological engineering in the faculty of applied science. "Our system will make it possible to remove and destroy these substances in the water supply before they can harm our health."

Catch and destroy

The UBC system combines an activated carbon filter with a special, patented catalyst that traps harmful chemicals and breaks them down into harmless components on the filter material. Scientists refer to this trapping of chemical components as adsorption.

"The whole process is fairly quick, depending on how much water you're treating," said Dr. Foster. "We can put huge volumes of water through this catalyst, and it will adsorb the PFAS and destroy it in a quick two-step process. Many existing solutions can only adsorb while others are designed to destroy the chemicals. Our catalyst system can do both, making it a long-term solution to the PFAS problem instead of just kicking the can down the road."

No light? No problem

Like other water treatments, the UBC system requires ultraviolet light to work, but it does not need as much UV light as other methods.

During testing, the UBC catalyst consistently removed more than 85 percent of PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid, a type of forever chemical) even under low light conditions.

"Our catalyst is not limited by ideal conditions. Its effectiveness under varying UV light intensities ensures its applicability in diverse settings, including regions with limited sunlight exposure," said Dr. Raphaell Moreira, a professor at Universität Bremen who conducted the research while working at UBC.

For example, a northern municipality that gets little sun could still benefit from this type of PFAS solution.

"While the initial experiments focused on PFAS compounds, the catalyst's versatility suggests its potential for removing other types of persistent contaminants, offering a promising solution to the pressing issues of water pollution," explained Dr. Moreira.

From municipal water to industry cleanups

The team believes the catalyst could be a low-cost, effective solution for municipal water systems as well as specialized industrial projects like waste stream cleanup.

They have set up a company, ReAct Materials, to explore commercial options for their technology.

"Our catalyst can eliminate up to 90 percent of forever chemicals in water in as little as three hours—significantly faster than comparable solutions on the market. And because it can be produced from forest or farm waste, it's more economical and sustainable compared to the more complex and costly methods currently in use," said Dr. Foster.

Reference: "Hybrid graphenic and iron oxide photocatalysts for the decomposition of synthetic chemicals" by Raphaell Moreira, Ehsan B. Esfahani, Fatemeh A. Zeidabadi, Pani Rostami, Martin Thuo, Madjid Mohseni and Earl J. Foster, 21 August 2024, Communications Engineering.

DOI: 10.1038/s44172-024-00267-4

The research was supported by an NSERC Discovery grant.

News

Scientists Finally Solve a 30-Year-Old Cancer Mystery Hidden in Rye Pollen

Nearly 30 years after rye pollen molecules were shown to slow tumor growth in animals, scientists have finally determined their exact three-dimensional structures. Nearly 30 years ago, researchers noticed something surprising in rye pollen: [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

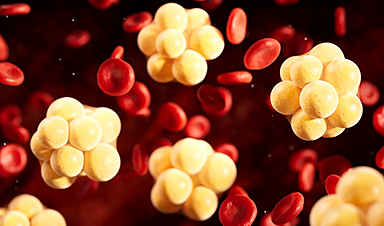

How lipid nanoparticles carrying vaccines release their cargo

A study from FAU has shown that lipid nanoparticles restructure their membrane significantly after being absorbed into a cell and ending up in an acidic environment. Vaccines and other medicines are often packed in [...]

New book from NanoappsMedical Inc – Molecular Manufacturing: The Future of Nanomedicine

This book explores the revolutionary potential of atomically precise manufacturing technologies to transform global healthcare, as well as practically every other sector across society. This forward-thinking volume examines how envisaged Factory@Home systems might enable the cost-effective [...]

A Virus Designed in the Lab Could Help Defeat Antibiotic Resistance

Scientists can now design bacteria-killing viruses from DNA, opening a faster path to fighting superbugs. Bacteriophages have been used as treatments for bacterial infections for more than a century. Interest in these viruses is rising [...]

Sleep Deprivation Triggers a Strange Brain Cleanup

When you don’t sleep enough, your brain may clean itself at the exact moment you need it to think. Most people recognize the sensation. After a night of inadequate sleep, staying focused becomes harder [...]

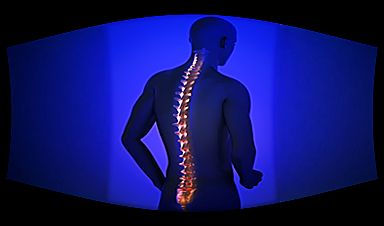

Lab-grown corticospinal neurons offer new models for ALS and spinal injuries

Researchers have developed a way to grow a highly specialized subset of brain nerve cells that are involved in motor neuron disease and damaged in spinal injuries. Their study, published today in eLife as the final [...]

Urgent warning over deadly ‘brain swelling’ virus amid fears it could spread globally

Airports across Asia have been put on high alert after India confirmed two cases of the deadly Nipah virus in the state of West Bengal over the past month. Thailand, Nepal and Vietnam are among the [...]

This Vaccine Stops Bird Flu Before It Reaches the Lungs

A new nasal spray vaccine could stop bird flu at the door — blocking infection, reducing spread, and helping head off the next pandemic. Since first appearing in the United States in 2014, H5N1 [...]

These two viruses may become the next public health threats, scientists say

Two emerging pathogens with animal origins—influenza D virus and canine coronavirus—have so far been quietly flying under the radar, but researchers warn conditions are ripe for the viruses to spread more widely among humans. [...]

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells in UCLA-led study Clues about extreme cases and omicron’s effects come from a cross-disciplinary international research team New research shows that after the [...]

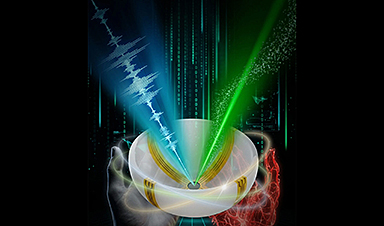

Smaller Than a Grain of Salt: Engineers Create the World’s Tiniest Wireless Brain Implant

A salt-grain-sized neural implant can record and transmit brain activity wirelessly for extended periods. Researchers at Cornell University, working with collaborators, have created an extremely small neural implant that can sit on a grain of [...]

Scientists Develop a New Way To See Inside the Human Body Using 3D Color Imaging

A newly developed imaging method blends ultrasound and photoacoustics to capture both tissue structure and blood-vessel function in 3D. By blending two powerful imaging methods, researchers from Caltech and USC have developed a new way to [...]

Brain waves could help paralyzed patients move again

People with spinal cord injuries often lose the ability to move their arms or legs. In many cases, the nerves in the limbs remain healthy, and the brain continues to function normally. The loss of [...]

Scientists Discover a New “Cleanup Hub” Inside the Human Brain

A newly identified lymphatic drainage pathway along the middle meningeal artery reveals how the human brain clears waste. How does the brain clear away waste? This task is handled by the brain’s lymphatic drainage [...]

New Drug Slashes Dangerous Blood Fats by Nearly 40% in First Human Trial

Scientists have found a way to fine-tune a central fat-control pathway in the liver, reducing harmful blood triglycerides while preserving beneficial cholesterol functions. When we eat, the body turns surplus calories into molecules called [...]