Increasing drug resistance could leave us powerless to fight infections we now consider routine, and scientists are urgently searching for answers.

It was just a urinary tract infection (UTI). Helen Osment, a fundraiser from Hertfordshire, had had them before and she knew the symptoms. When she called the doctor with pain, a burning sensation and blood in her urine, they prescribed a course of antibiotics – a few days of nitrofurantoin.

But this time, her UTI didn’t go away. It got worse. The pain was bad and she started feeling feverish. As her symptoms failed to improve, she felt uncomfortable and miserable. “I think it can affect you mentally when you have one, it can make you feel quite sort of down and low,” she says.

Her doctor tried another antibiotic, trimethoprim, but the infection remained. Still feeling awful, she asked the doctor for “something stronger”. Options were limited by the fact that Osment had been deemed allergic to penicillin as a child, and this was flagged on her records (though like many who are flagged as allergic, she later turned out not to be). She was prescribed ciprofloxacin but reacted badly: she felt heart palpitations and pain in her knee, which turned out to be tendonitis, a potential side-effect of the drug. She visited a walk-in centre, where she was told to stop taking it and was put on a longer course of nitrofurantoin.

Her condition deteriorated. Feverish and in so much pain she couldn’t even pick up her baby, she ended up in A&E. “I was thinking, oh surely they’ll just give me some more antibiotics,” she says. “I didn’t realise how ill I was.” The mastitis had formed a large abscess and Osment had developed sepsis – a life-threatening condition caused by the body’s response to an infection. Luckily, this was caught early, and after being hospitalised and put on a different antibiotic intravenously, she beat the infection and recovered.

“It just goes to show that it can happen to anybody, and things can escalate very quickly,” Osment says. She now shares her story through the charity Antibiotic Research UK, to help raise awareness of antimicrobial resistance.

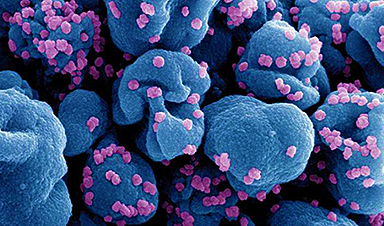

When Covid-19 began to spread around the globe, it was something we hadn’t seen before and we had no medicines to defend ourselves against it. But it’s not only new pathogens, like Sars-CoV-2, that pose a threat to global human health. Antimicrobial resistance means that existing bugs – ones we perhaps don’t worry too much about – are becoming resistant to the treatments we have come to take for granted, such as antibiotics. As this resistance becomes more common, we could find ourselves in a similar situation: facing infectious diseases with limited treatment options.

Our experience under Covid-19 may have given us a glimpse of that future. “It shows what the world would be like if we had resistance to all known antibiotics,” says Jessica Boname, former head of antimicrobial resistance at the UK’s Medical Research Council. “We would be in the Covid-19 world.”

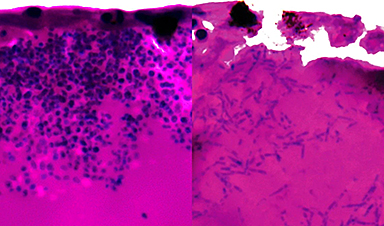

The term antibiotic resistance refers specifically to bacteria becoming resistant to antibiotics. Antimicrobial resistance is a broader term that also covers other microbes such as fungi, parasites and viruses.

Today, if we get an infection, we generally expect that we can go to the doctor and get some medicine to treat it. But if the microbes causing the infection are resistant to that medicine, the infection may not go away. We might go on to try another drug, and another, and another, but if the microbes are resistant to those too, we’re back at square one. Microbes that are able to resist multiple antimicrobials are sometimes referred to as “superbugs” – and they can be very difficult to treat.

The stakes are high. If antimicrobial resistance is left to rise unchecked, we may no longer be able to knock out common infections with a simple prescription. Illnesses caused by resistant pathogens will require longer, more costly treatment. In more and more cases, we may not be able to treat a resistant infection at all.

And it’s not just routine infections that will become more dangerous as we lose more antimicrobials from our medical arsenal. Much of modern medicine is built on the assumption that we can easily fight or prevent infection. If this is no longer the case, these foundations start to crumble.

Take surgery: antibiotics are given as a preventative measure before and after many operations that have a high risk of infection, such as hip replacements, organ transplants or Caesarean sections. If we can no longer count on antimicrobials being effective, surgery will become much more risky. In some cases, it may be unviable: the risk of getting an untreatable infection will simply be too high.

For most infections, we have multiple lines of defence. If one antimicrobial doesn’t work, you try another, then another, and so on until you reach those that are held back as a last resort, to be used only in extremely limited cases so as to prevent resistance from occurring. As these antimicrobials are struck down by resistance, the obvious solution would be to make new ones. But we aren’t developing them fast enough.

According to the World Health Organisation, lack of innovation and funding is a major concern, with most new products in development showing little extra benefit and few targeting some of the most urgent infections.

Most of the antimicrobial substances that we commonly use today were found in the 40s and 50s, soon after penicillin – a “golden era” for antibiotic discovery. But in the following decades, discoveries of new antibiotics were few and far between. The low-hanging fruit had been found and scientists were getting frustrated at discovering the same compounds again and again.

In the latter part of the 20th century, a new method was adopted. Rather than screening natural compounds to search for antimicrobial substances, scientists decided to try a more targeted approach. They set out to look specifically for compounds that inhibited pathways essential to the function of bacteria. If you know a bacterium needs to create a certain enzyme to thrive, for instance, then finding a compound that inhibits the production of this enzyme could give you a promising lead for a new antimicrobial drug. Researchers turned their attention to synthetic compounds in the vast chemical libraries of research groups and pharmaceutical companies.

It’s an approach that has been successful for discovering many kinds of drugs, but it didn’t really work for antimicrobials. “They were new technologies at the time, we thought they were going to generate lots of really useful compounds,” says Mathew Upton, a professor of medical microbiology at the University of Plymouth. “And they basically generated nothing at all.”

It’s not that we didn’t find anything – promising compounds were identified – but when tested they just didn’t work in actual bacteria. And so the focus turned once again to natural substances, making the most of the tiny, living antibiotic factories in the environment all around us. These days, the way many researchers find new antibiotics is not all that dissimilar to Alexander Fleming’s observation of mould on a sample dish, albeit rather more deliberate.

The reason for searching in places so far removed from our everyday environment is that it increases the chance of finding a truly novel antibiotic compound, Upton explains. Often, researchers can find a substance with promising antibiotic properties, but once they’ve gone through the hassle of growing the microbe in the lab and purifying the compound, they find out it is the same as, or similar to, an existing antibiotic – and will therefore likely be disarmed by the same resistance mechanisms.

“If a compound is the same as something we’ve seen before, or very related to it, it’s probably not going to be worth developing, because any resistance mechanism that is already out there will undermine it as soon as we use it in the clinic,” Upton says.

But we don’t always need to look so far away from home. Upton is currently working with one compound that was found in a sample taken from the surface of human skin.

But ultimately, the things that could have the most impact are the ones we already know about – like access to clean water and sanitation, infection prevention and control measures, and improved access to existing vaccines and treatments. Similarly, if we can improve infection control measures in hospitals, we will reduce the spread of hospital-acquired infections. When people do get infections, we need to be better at treating them – using the right antimicrobials in the right patients, at the right doses. We also need to reconsider our use of antimicrobials in agriculture and the environment.

Individuals can refrain from asking for antibiotics when they have a cold and follow the instructions when they are prescribed them. Prescribers can make sure they’re sticking to stewardship guidelines.

A multitude of solutions are needed to address many different issues. Just as we have seen with the Covid-19 pandemic, we need researchers, clinicians, engineers, politicians, behavioural scientists and economists to work together across borders.

News

AI Helped Scientists Stop a Virus With One Tiny Change

Using AI, researchers identified one tiny molecular interaction that viruses need to infect cells. Disrupting it stopped the virus before infection could begin. Washington State University scientists have uncovered a method to interfere with a key [...]

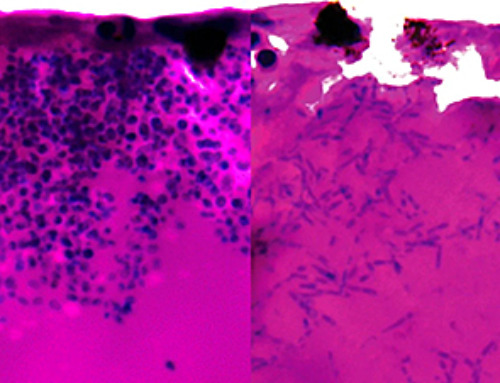

Deadly Hospital Fungus May Finally Have a Weakness

A deadly, drug-resistant hospital fungus may finally have a weakness—and scientists think they’ve found it. Researchers have identified a genetic process that could open the door to new treatments for a dangerous fungal infection [...]

Fever-Proof Bird Flu Variant Could Fuel the Next Pandemic

Bird flu viruses present a significant risk to humans because they can continue replicating at temperatures higher than a typical fever. Fever is one of the body’s main tools for slowing or stopping viral [...]

What could the future of nanoscience look like?

Society has a lot to thank for nanoscience. From improved health monitoring to reducing the size of electronics, scientists’ ability to delve deeper and better understand chemistry at the nanoscale has opened up numerous [...]

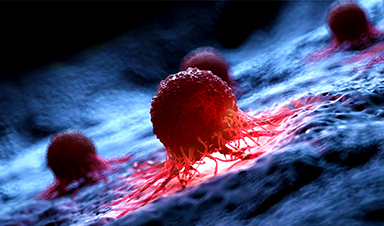

Scientists Melt Cancer’s Hidden “Power Hubs” and Stop Tumor Growth

Researchers discovered that in a rare kidney cancer, RNA builds droplet-like hubs that act as growth control centers inside tumor cells. By engineering a molecular switch to dissolve these hubs, they were able to halt cancer [...]

Platelet-inspired nanoparticles could improve treatment of inflammatory diseases

Scientists have developed platelet-inspired nanoparticles that deliver anti-inflammatory drugs directly to brain-computer interface implants, doubling their effectiveness. Scientists have found a way to improve the performance of brain-computer interface (BCI) electrodes by delivering anti-inflammatory drugs directly [...]

After 150 years, a new chapter in cancer therapy is finally beginning

For decades, researchers have been looking for ways to destroy cancer cells in a targeted manner without further weakening the body. But for many patients whose immune system is severely impaired by chemotherapy or radiation, [...]

Older chemical libraries show promise for fighting resistant strains of COVID-19 virus

SARS‑CoV‑2, the virus that causes COVID-19, continues to mutate, with some newer strains becoming less responsive to current antiviral treatments like Paxlovid. Now, University of California San Diego scientists and an international team of [...]

Lower doses of immunotherapy for skin cancer give better results, study suggests

According to a new study, lower doses of approved immunotherapy for malignant melanoma can give better results against tumors, while reducing side effects. This is reported by researchers at Karolinska Institutet in the Journal of the National [...]

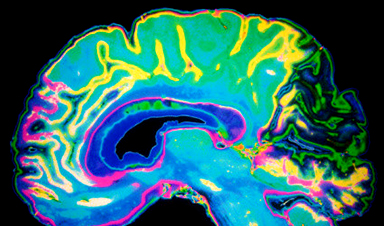

Researchers highlight five pathways through which microplastics can harm the brain

Microplastics could be fueling neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, with a new study highlighting five ways microplastics can trigger inflammation and damage in the brain. More than 57 million people live with dementia, [...]

Tiny Metal Nanodots Obliterate Cancer Cells While Largely Sparing Healthy Tissue

Scientists have developed tiny metal-oxide particles that push cancer cells past their stress limits while sparing healthy tissue. An international team led by RMIT University has developed tiny particles called nanodots, crafted from a metallic compound, [...]

Gold Nanoclusters Could Supercharge Quantum Computers

Researchers found that gold “super atoms” can behave like the atoms in top-tier quantum systems—only far easier to scale. These tiny clusters can be customized at the molecular level, offering a powerful, tunable foundation [...]

A single shot of HPV vaccine may be enough to fight cervical cancer, study finds

WASHINGTON -- A single HPV vaccination appears just as effective as two doses at preventing the viral infection that causes cervical cancer, researchers reported Wednesday. HPV, or human papillomavirus, is very common and spread [...]

New technique overcomes technological barrier in 3D brain imaging

Scientists at the Swiss Light Source SLS have succeeded in mapping a piece of brain tissue in 3D at unprecedented resolution using X-rays, non-destructively. The breakthrough overcomes a long-standing technological barrier that had limited [...]

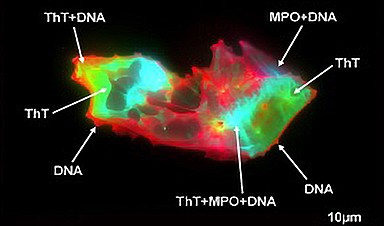

Scientists Uncover Hidden Blood Pattern in Long COVID

Researchers found persistent microclot and NET structures in Long COVID blood that may explain long-lasting symptoms. Researchers examining Long COVID have identified a structural connection between circulating microclots and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). The [...]

This Cellular Trick Helps Cancer Spread, but Could Also Stop It

Groups of normal cbiells can sense far into their surroundings, helping explain cancer cell migration. Understanding this ability could lead to new ways to limit tumor spread. The tale of the princess and the [...]